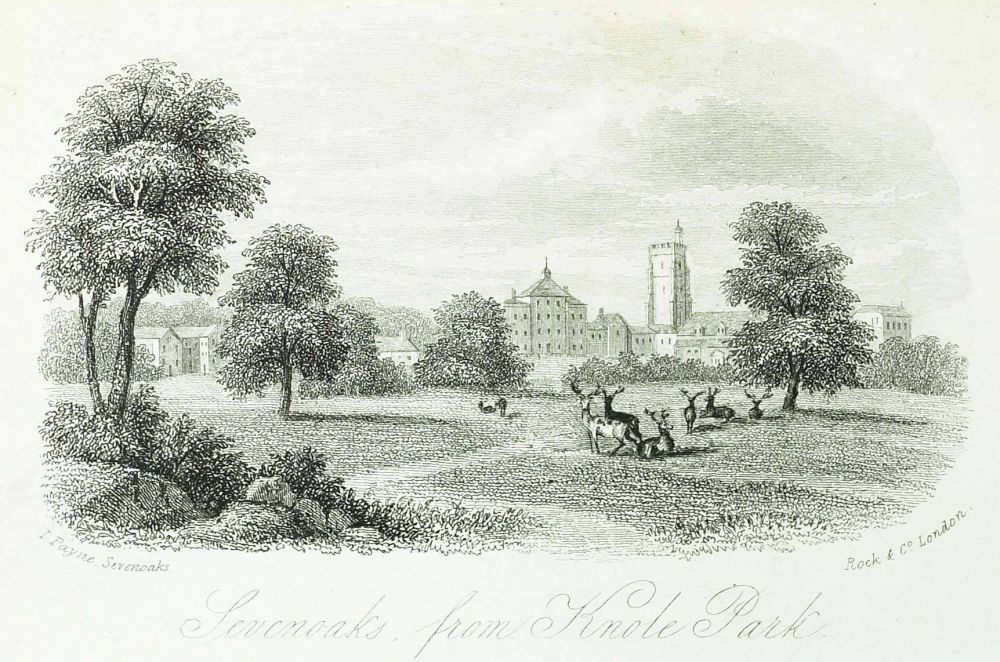

In the mid-1950s, Charles, 4th Baron Sackville gave to Sevenoaks School two items of significance: the main lease of Duke’s Meadow (thereby creating an all-year sports facility) and a small strip of land behind what is now the Marley Sports Centre, ‘in order that its view of Knole House and the park might be preserved’ [Brian Scragg, Sevenoaks School a History, 1993]. The latter was a visual reminder of a relationship between the two properties which had long existed, since at least the mid-15th century when the school had begun building its schoolhouse and almshouses under the terms of William Sevenoke’s 1432 will and 1456 when Henry Bourchier had begun turning the de Knolle family’s small stone farmhouse into an archiepiscopal palace and enclosed the deer park. Until the 19th century the existing records are too sparse to be able to discern the extent of contact between the school and Knole. Just occasional mentions of a rental being paid to the Estate in the Governors’ Minutes, names of the incumbent Duke of Dorset as one of the four Wardens charged with managing the school and an enduring myth that a member of the Knole household, a Chinese page called Huang Ya Dong, was educated at the School in the late 1770s. However in 1877 a formal link between the two properties was clearly defined when under the terms of a new scheme of governance for the school it was stipulated that one of the new governing body should always be the Lord of the Manor of Knole; so for the next 130 years a succession of Barons Sackville sat on the Board of Governors in a capacity as its Hereditary Governor, Chairman or President. In theSennockian of April 1928, headmaster James Higgs Walker made reference to the bond between the two establishments created by this post when he spoke of how the ‘early part of this term was darkened for us by the illness and death of [Lionel, 3rd] Lord Sackville. He was a very human Chairman of Governors and the school will miss his friendly presence at the various athletic events in Knole Park which he not only allowed but encouraged’. The connections have continued right up to the present day: cross country running in the park; the exploding parachute bomb caught in one of the park trees during the Second World War that shattered the windows of School House (now Old School); the purchase of the Knole Dower House in 1947 that is now known as Manor House; Sackville, the new day house of 1955; the Sackville Theatre built in 1981; and not forgetting the creation of another school myth – the subterranean cavern that was discovered under the new Sanatorium in 1931 which was surely a secret passage to Knole house. Recently found in the archives are two unique items which also illustrate the relationship between Knole and the School: printed copies of the speeches Vita Sackville-West and her husband, Harold Nicolson, gave when they presented the prizes at the Annual Speech Day in 1928 and 1955 respectively. Vita Sackville-West’s life and literary career were interwoven inextricably with Knole – born there in March 1892 it was her home until she married in its chapel in 1913. Her purchase of Long Barn in Weald village two years afterwards ensured that she did not completely lose her connection with the Sevenoaks area until she moved to Sissinghurst in the 1930s. The social class in which Vita grew up meant that she and her family had little daily contact with the local populace but there were occasional tea parties and dancing classes held at Knole with local children. Events at ‘the big house’ that brought guests such as the Prince of Wales, Ellen Terry and Winston Churchill down the entrance lane beside the school would surely have provided interest for its pupils. When Vita gave her Speech Day address on 1 August 1928 she had recently been forced to cut her ties with Knole following the death of her father in the previous January; it was ‘the first great sorrow of her life…that by an accident of gender,’ she could never inherit Knole [Victoria Glendinning, Vita, 1983]. She spoke to the boys about the ‘English character’, reported the Sevenoaks Chronicle: ‘There was one form of conventionality said Mrs Nicolson with which she had no patience…that which made people take all their opinions second hand. They should think for themselves, they should avoid all this parrot like repetition of other people’s ideas’. Harold Nicolson’s speech, ‘A Time to Flower’, 27 years later, spoke of his own unhappy schooldays and encouraged those who did not feel they excelled in anything at school to have patience for they would have hidden qualities which would appear later in life: ‘I find [such boys]…a far more interesting audience than the successful school boy…Believe me when I say that those boys who may seem clumsy, or bad at games, or even a little mad, may turn out to be far more valuable people than university blues or even cinema stars.’